Who came first, the olive ridley sea turtle or the Ostional community?

The literature says that it was the community, more than a hundred years ago, founded in the year 1902. The arrival of Lepidochelys olivacea, scientific name of the olive ridley turtle, could have been in 1935, according to one of the oldest inhabitants of Ostional as well as scientific publications in 1959, and in the mid-1960s.

There are no exact dates for these two arrivals, but what is indisputable is that the Ostional Wildlife Refuge (RVS Ostional) was the last to arrive, officially established in 1983.

The objective of the refuge has always been the protection of the spawning and reproduction area of the olive ridley turtle and other marine resources. For this purpose, the refuge spans 468 hectares of land, 8,000 marine hectares, and 16 km of coastline. From the perspective of many families living in that section of the northern Pacific of Costa Rica at the time, an external force was taking away their ownership of their land, but also standing between them and a resource they had always considered their own: turtle eggs.

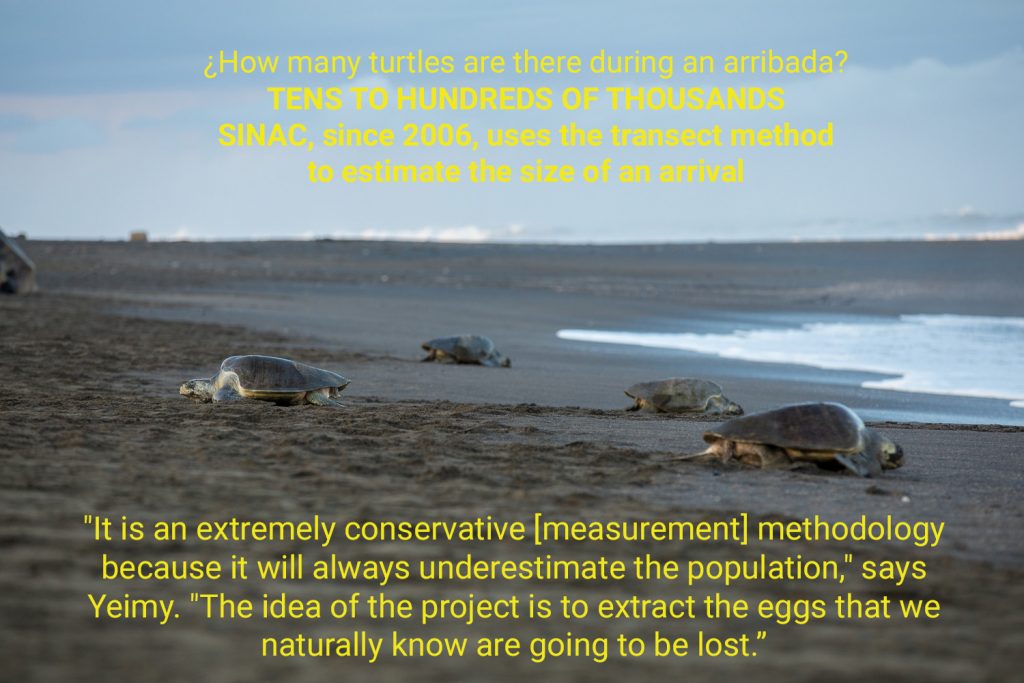

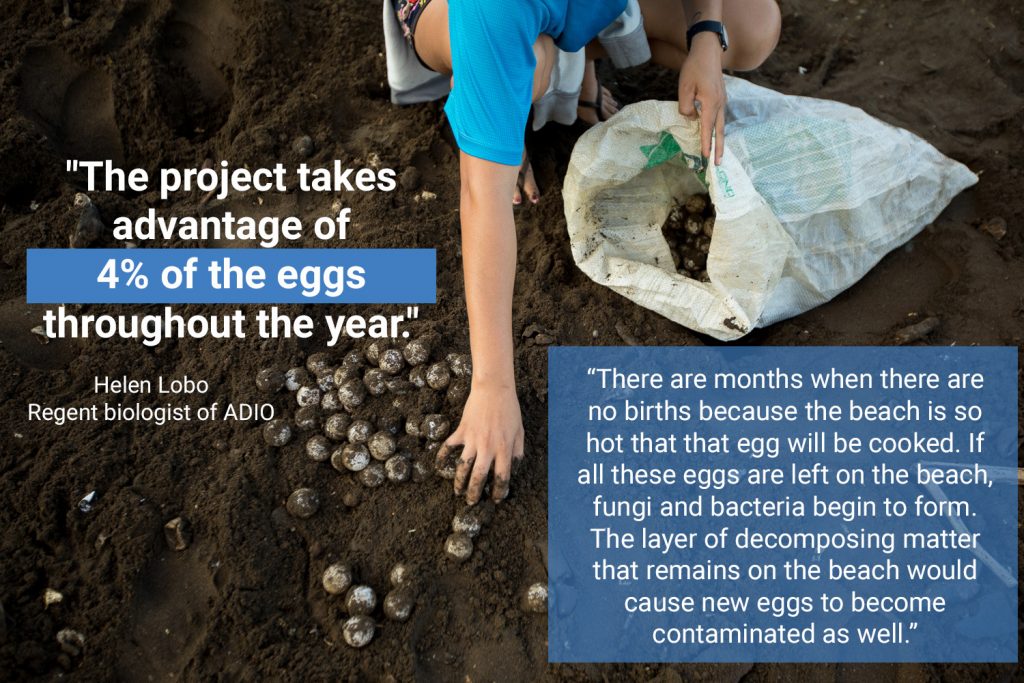

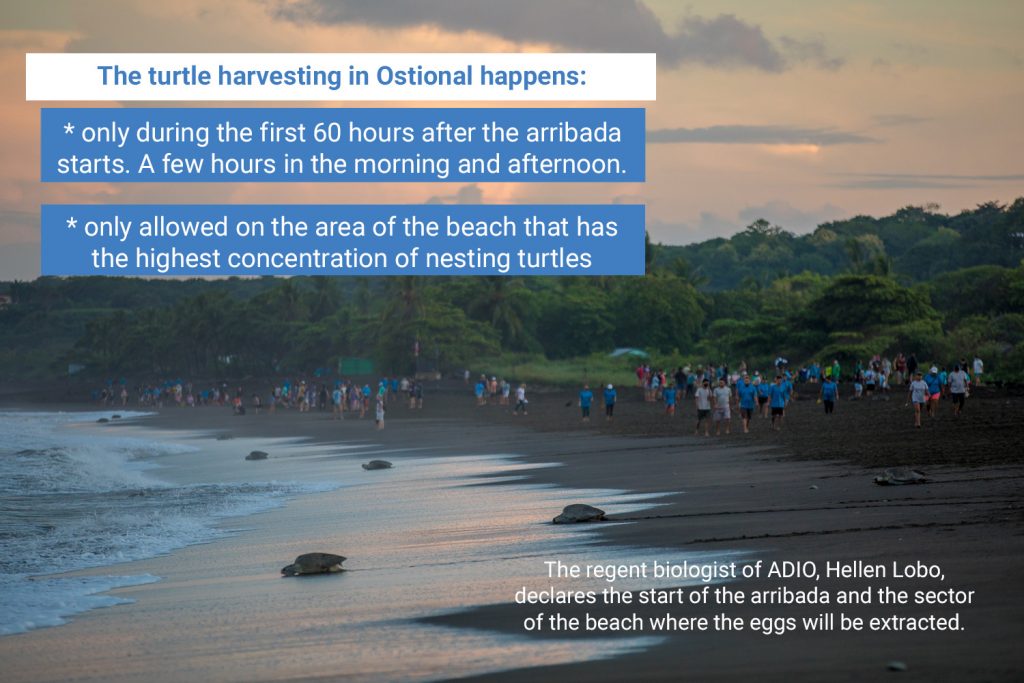

“At that time,” says Yeimy Cedeño, administrator of RVS Ostional, “the protected area invaded a community that already existed.” However, as she herself says, this “invasion” was based on scientific studies, led primarily by Douglas Robinson from the University of Costa Rica (UCR). Those studies took into account the relationship between people and turtle eggs, providing the scientific legitimacy for Law 7064, signed in 1987. The law permitted the sale of olive ridley eggs from RVS Ostional—something that had been prohibited nationwide in 1948.

Scientific legitimacy

The research that has been carried out in Ostional since the 1970s has included a continuous analysis of whether the controlled extraction of eggs carried out by the community is detrimental to the species.

In the past, this abundance of eggs led to harmful extractive practices.

“My father had about 100 pigs, and the food they gave the pigs was turtle eggs,” says Elmith Molina, daughter of Norberto Molina, one of the community leaders who promoted the legalization of egg extraction in Ostional. “At 5:30 am, people opened the gates of the pig pens so the pigs could run out to the beach and begin to dig for eggs.”

Elmith and Yeimy say that before the creation of the protected area, the eggs were being consumed excessively in Ostional. Not only were pigs were released on the beach to feed themselves, but eggs were also sold to outsiders.

“You smuggled eggs only at night,” Elmith recalls from her childhood. “Everyone would take out their bags and go into a bush to hide them. Trucks came from San José to buy the illegal turtle eggs: they took the eggs on trust. There were buyers who were honest, or perhaps they felt sorry for the poverty of this town; they might return to pay.” However, ostionaleños often ended these transactions without eggs or money.

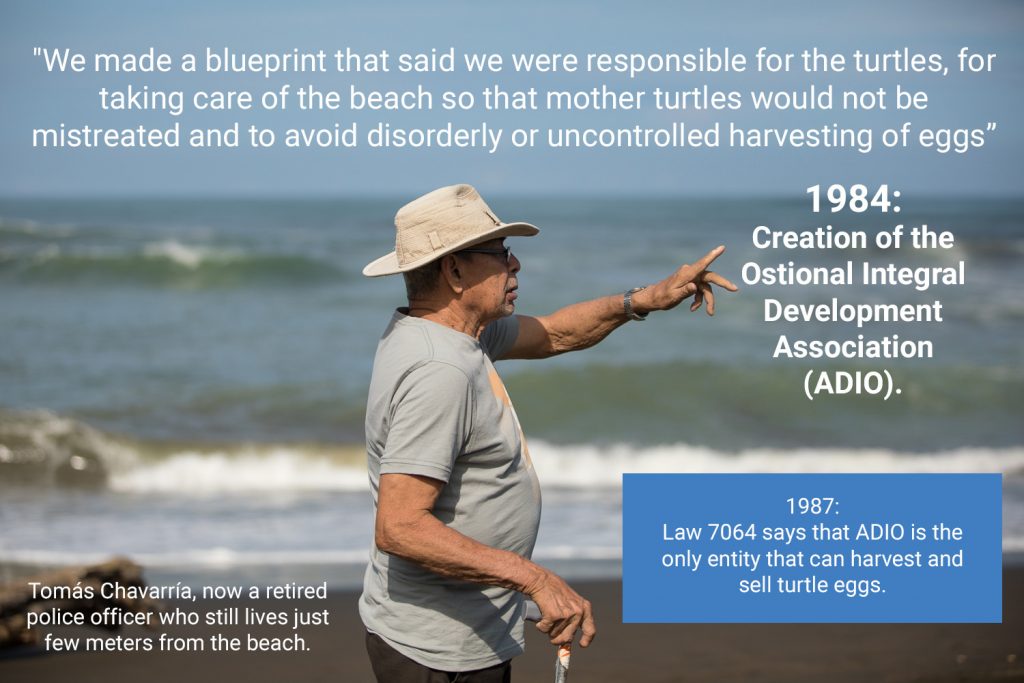

Tomás Chavarría, Basilio Vega and Norberto Molina, together with researcher Douglas Robinson from the UCR, led the effort to demonstrate that the controlled extraction of turtle eggs was viable and beneficial for the community and the protection of the turtle.

The creation of ADIO was not an easy task.

“We had to walk or travel on horseback to win over all our neighbors,” says Tomás, who also had to travel to San José to negotiate with legislators and Cabinet ministers, arguing that the community would make rational use of the resource to generate a stable income for its residents. “[The villagers] supported themselves in an illegal way [with turtles] and they felt that we were trying to set the law against them.”

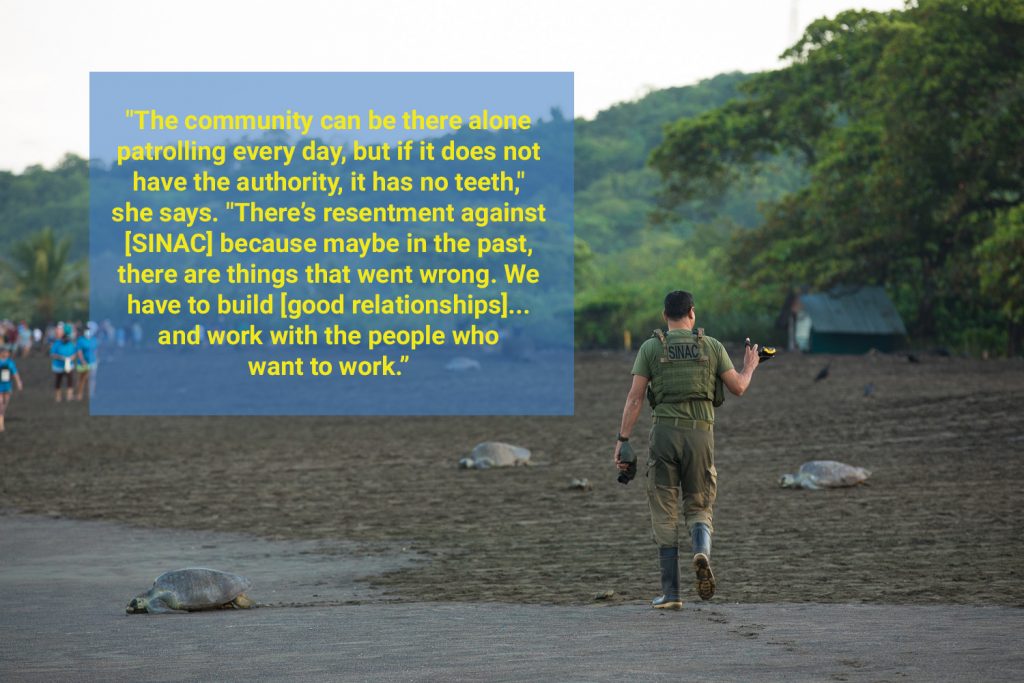

“ADIO has been such a visionary community organization,” says Yeimy, who since 2016 has facilitated joint efforts between her employer, the National System of Conservation Areas (SINAC), and a community that has had to face many challenges over nearly 40 years. “This community has been self-managed in its development, with all that that implies—socially, environmentally, and economically—and with terrible limitations, because the refuge just fell on top of them. It limited everything they do.”

The commitment

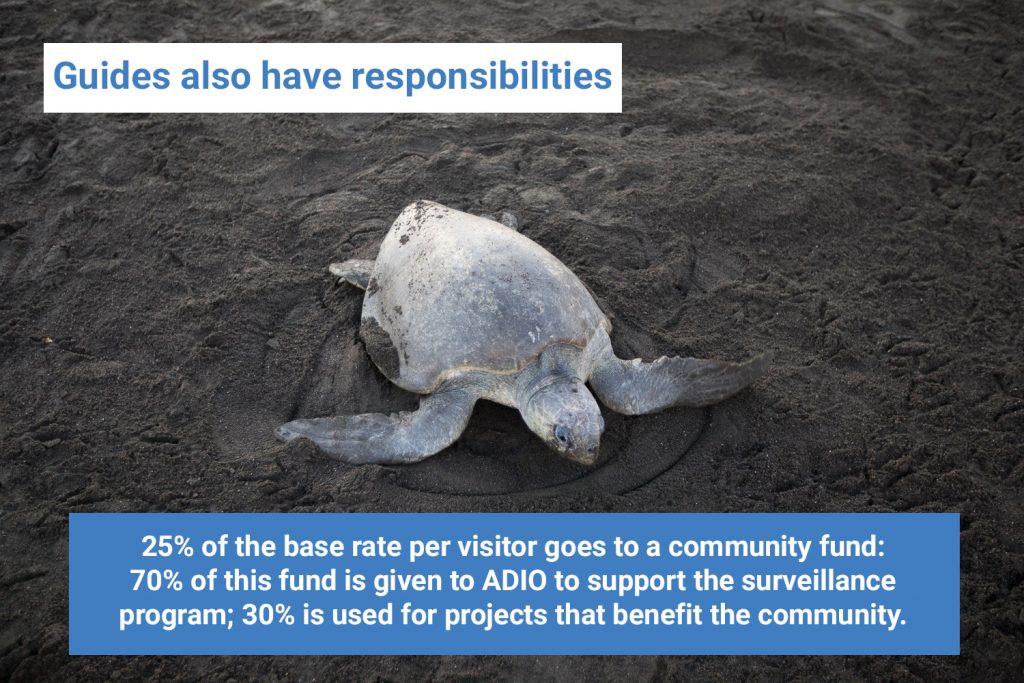

The extraction of turtle eggs in Ostional is organized and supervised by four actors: ADIO, SINAC, UCR and the Costa Rican Institute of Fisheries and Aquaculture (INCOPESCA). In accordance with five-year action plans for turtle egg extraction, each of these actors has specific responsibilities that allow them not only to organize the process, but also to implement constant improvements.

This joint, organized and systematized work allowed the Inter-American Convention for the Protection and Conservation of Sea Turtles, which Costa Rica signed in 1997, to recognize Ostional in 2015 as an exception for the sale of turtle eggs, accompanied by specific recommendations for improvement.

Ostional has drawn attention nationally and internationally since the 1970s, when the massive and synchronized nesting of olive ridleys on its beaches began to become well known. To this day, there are those who question and criticize the extraction of eggs in Ostional.

“You may not agree; you may not want to consume” the eggs, says Yeimy, “but what is not acceptable is for you to say, ‘They are stealing the eggs and they are affecting the population of sea turtles,’ because that is not true.”

According to Hellen, Yeimy, and dozens of scientific publications, the turtle egg extraction project is more than an economic model. It is also a management and conservation project.

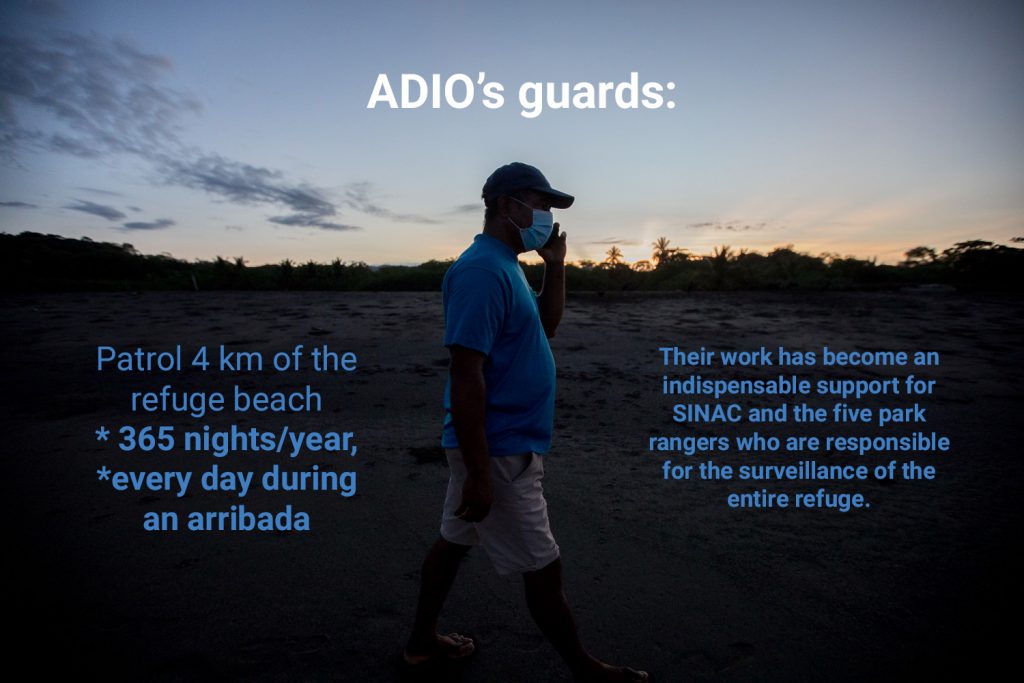

“The community takes on a lot of responsibilities and commitments to the refuge,” says Yeimy. “As civil servants, we do not have that capacity, but when we work collaboratively, we can achieve things.”

The profits

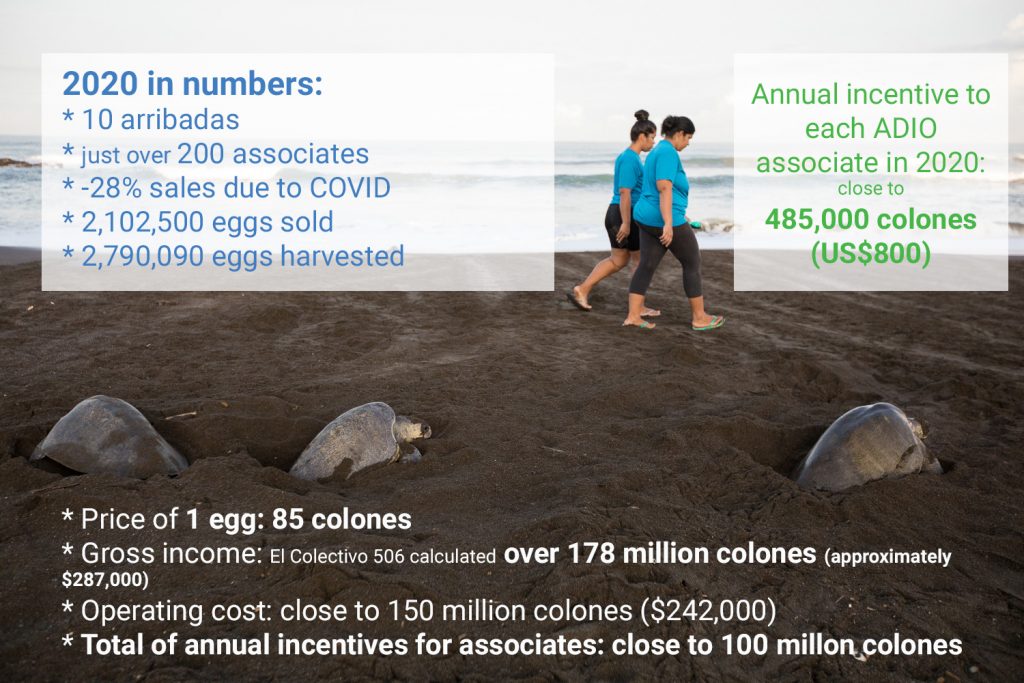

The quantity of eggs that are harvested during arribada depends mainly on demand. ADIO has succeeded in creating an ordering system that not only reduces the waste of extracted eggs, but has also forced resellers to place regular orders and not manipulate supply and demand.

ADIO associates must be over 15 years of age, live in Ostional, and demonstrate roots in the community through their ancestry or length of residence.

However, not all associates are required to work. People over 70 years of age or with severe disabilities receive the incentive as a lifetime pension, and pregnant women have a three-month maternity leave. According to Keren Matarrita, president of ADIO, approximately 40 members fall into these categories.

Those members with other circumstances that prevent them from carrying out their duties may opt for a lesser incentive in exchange for less demanding, or fewer, tasks. In addition, associates who are in college outside of the community continue to receive the full incentive.

Keren was a beneficiary of this support when she was a foreign trade student at the National University in Nicoya.

“When I was young, I wanted to become [an associate],” she says. “I didn’t know what it was like to work there: it’s hard. But when the first payment came, I said, ‘It was worth all the sacrifice’ …Those payments helped me a lot when I was studying. I had extra income for college.”

The next largest operating expense for ADIO is incentive pay for the ADIO Guard Corps. The guards, along with SINAC, deter and denounce the illegal looting of eggs and the mistreatment of adult turtles. They also alert authorities when a nesting event begins, and when turtles are born.

In 2020, associates also extracted another 650,000 eggs for consumption by the associates themselves and as a donation to families in the surrounding communities. Due to the pandemic, ADIO donated more eggs than in previous years (25% of the total harvest) to help local families who lost their income.

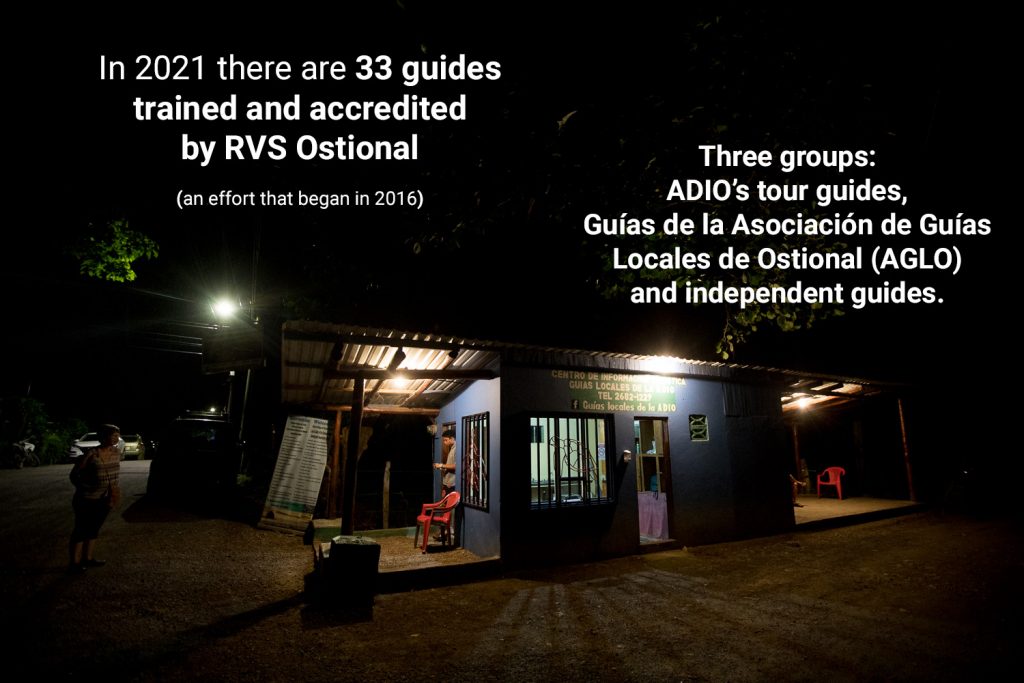

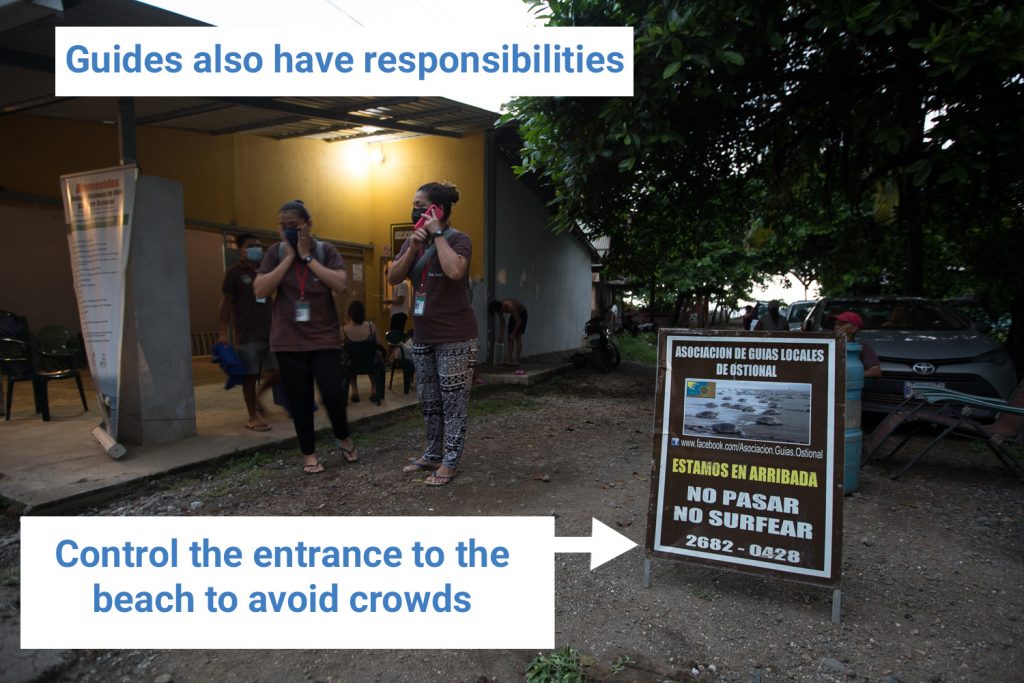

Tourist guides are another important stakeholder as collaborators and beneficiaries. RVS Ostional regulations require that during an arribada, visitors can enter the beach only if they are accompanied by a local guide.

The guides also have responsibilities that have been agreed upon and implemented in recent years, especially during 2020.

According to Elmith Molina, vice president of AGLO and a local guide since 2002, AGLO participates in beach cleaning and caring for the turtles on a specific area of the beach that has been defined by MINAE.

The endless challenges

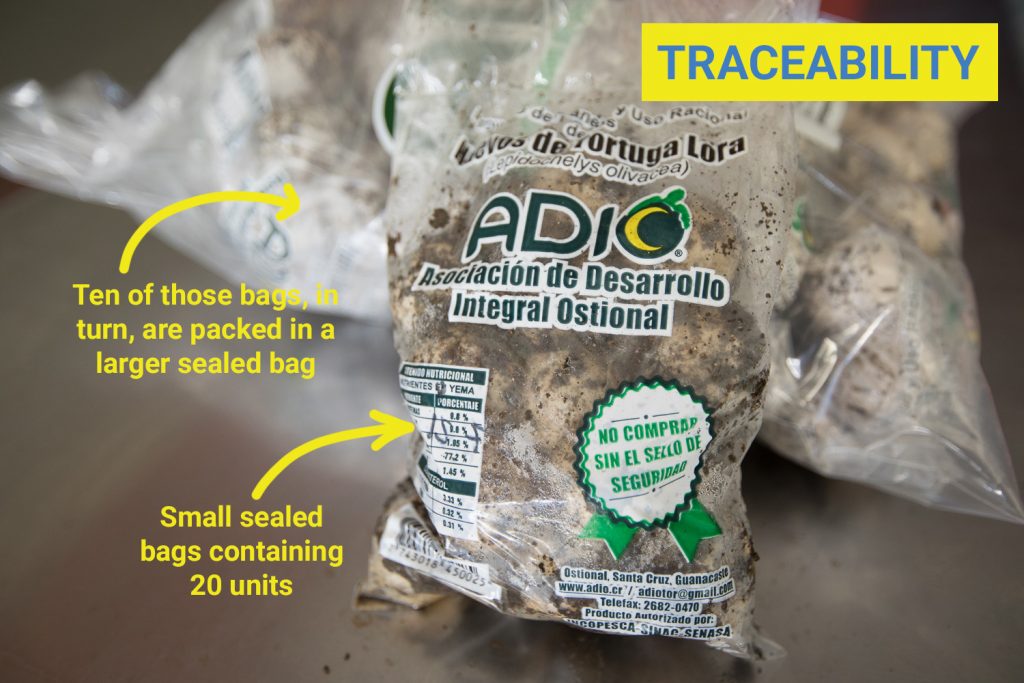

The traceability of turtle eggs once they leave Ostional is a significant challenge. This process seeks to guarantee—not only to national and international authorities, but also to final consumers—that the only turtle eggs sold in Costa Rica come from this project.

ADIO’s honorary members, who are the intermediaries that sell the product around Costa Rica, buy the 200-unit bags. The smallest quantity they are allowed to sell are the 20-unit sealed bags. They carry invoices with all of the traceability information, and must deliver this information to their buyers. A final consumer can buy a 20-unit bag at a farmer’s market, the supermarket, or any other establishment, but if the eggs are displayed outside the bag, the sale and purchase become illegal. In the case of a bar or restaurant that sells eggs for immediate consumption, it is the responsibility of the establishment to keep the respective documentation (bags and invoices), and it is the right and responsibility of the end consumer to request such documentation.

However, these traceability processes still need to be improved.

“What’s needed here is more awareness,” says Hellen, the regent. “There are many people in this country who do not know that the Ostional turtle egg can be sold and eaten, and that it is helping the conservation and economy of a town.”

Another challenge relates to innovation, not only in marketing but also in product development.

Associates “have enormous potential to start a business,” says Yeimy, the refuge manager. “There are still many limitations and abilites that they do not have.”

However, Keren says that ADIO’s members and, in particular, its board of directors of ADIO are do not lack for training opportunities. She says the problem lies in openness and adaptability to change and innovation.

Another important challenge is improving the project’s profits. ADIO’s operating costs and obligations are significant, and the profits for associates are low. Hellen and Keren participated in a National Training Institute (INA) class that showed them that the price at which they sell their product is too low.

A 200-unit bag now costs 17,000 colones (about $27). The study carried out with INA indicated that the bag should be worth approximately $2 more. However, the association decided not to raise the price. They don’t want to lose customers.

The magic recipe

Keren remembers that according to her grandmother, ther great-grandparents decided to come to live in Ostional because “they heard that there was something there. There were eggs. There was something to work with. Where they lived, there was nothing, so they came and did what other people were doing: illegal egg removal.”

The first ingredient in Ostional’s magic recipe is that basic resource. The second has been the commitment of all the participants.

“Here, it’s about giving and receiving,” says Keren. “What we receive from the turtle, we have to give back, because otherwise it doesn’t work. You have to be patient, committed, take responsibility, because if we all want to do it and in the end no one is responsible, it doesn’t work.”

For Yeimy, the secret is in the interdependence of the parties.

Rigorous scientific research, according to Yeimy and Hellen, has also been key in Ostional’s success—success that has helped keep residents from leaving town.

“Ostional is the coastal community with the lowest emigration rates in the area, because they have a source of income here—not only of money, but of food,” Hellen says.

She adds that the community values the project and is proud of the use made of the resource.

“At [ADIO] assemblies, I have seen how these initiatives are generated by the people themselves,” she says. “In Costa Rica, we have amassed many years of working for the conservation of wildlife, of protected areas. Why not start seeing what you can and can’t accomplish with them?”